Päivi Hietanen

March 2023

Design has long been one of Helsinki’s key tools for reforming the city. However, this work is not carried out alone. Finnish design agencies from which we buy design services for different needs are an important part of our network. A key tool in this work is the partnership agreement.

The benefit of the partnership agreement is that the service can be procured from partners selected through competitive bidding for a period of four years at a time, hourly prices have been agreed and complex data protection issues, for example, can be resolved centrally. The arrangement also facilitates a partnership between the customer and the agency: the agency becomes familiar with its customers, and the customer receives the services they need reliably.

Design cannot be purchased ready-made off the shelf. Design is a creative, multi-professional effort aimed at reforming activities.

Typically, understanding of the problem to be solved deepens during the process, and the solution is created through co-design. That is why it is not always known what the outcome will be when procuring design. It is therefore essential to describe the problem to be solved, not the solution, in the invitation to tender. This is where design differs from the procurement of many other expert services, such as commissioning a study.

The special characteristics of design make procurement not only challenging, but also extremely interesting.

At the City of Helsinki, design is procured by both divisions and the City Executive Office. Design procurement is also supported. Helsinki Lab, our own internal design team, supports city staff in the projectising of design projects, tendering and selecting the most suitable design agency. In the projectising phase, it is important to understand the root causes of the problem and development as a whole: what the actual issue is and what will ultimately change in the activities in question.

In addition to consulting, we also offer the city developers ‘design radar’ workshop that will be organised for the project team. It addresses the root causes and overall nature of the problem and creates a common understanding and vision for the project team for the future.

What does the City need?

Last year, we started a competitive tendering process for a new partnership agreement on service design. This was the third time we had run such a process. The objective was that this four-year agreement would respond to future challenges of the City. That is why we wanted to understand how the City has used design previously, and above all what is needed in the future.

Initially, we examined the procurements for the previous contract period in all divisions and in the City Executive Office in detail. This exposed the range of purposes of design in the City. The survey highlighted the scope of digital design procurements and the fact that design was used for a wide range of communication purposes.

We also collected key indicators from previous years. The calculations showed that design procurements had increased ninefold since 2016 when our first partnership agreement entered into force. The City Executive Office and the Culture and Leisure Division have purchased the most design.

The review of design procurements highlighted the variety of purposes that Helsinki has used design for. In 2021, design procurements amounted to 3.6 million euros. (Picture in Finnish)

The background research continued with interviews, which enabled us to map staff experiences of the use of the partnership agreement and views on future needs. We also benchmarked other cities and public administration actors with similar agreements. We gathered the views of the design offices through market dialogue.

The themes that emerged clearly in the discussions were strategic design, futures thinking, data and knowledge management. The importance of digital development was unwavering. There are many larger and smaller facility projects on the horizon, and the aim is to invest in their user participation.

The constantly changing operating environment challenges the services provided by the City, and agility and change management are needed.

We also saw that we needed closer links between service development and the renewal of the City’s own operations.

The impact of design activities and impact assessment were identified as challenges. This seems to be a common issue in the sector, and it has been discussed for as long as I can remember. If the impact is not known, it is impossible to assess whether the work carried out was useful. This challenge is related to all development activities. The benefits of design should also be demonstrated to allow the sector to grow and become stronger at a strategic level and in management forums. Effectiveness must be both sold and purchased.

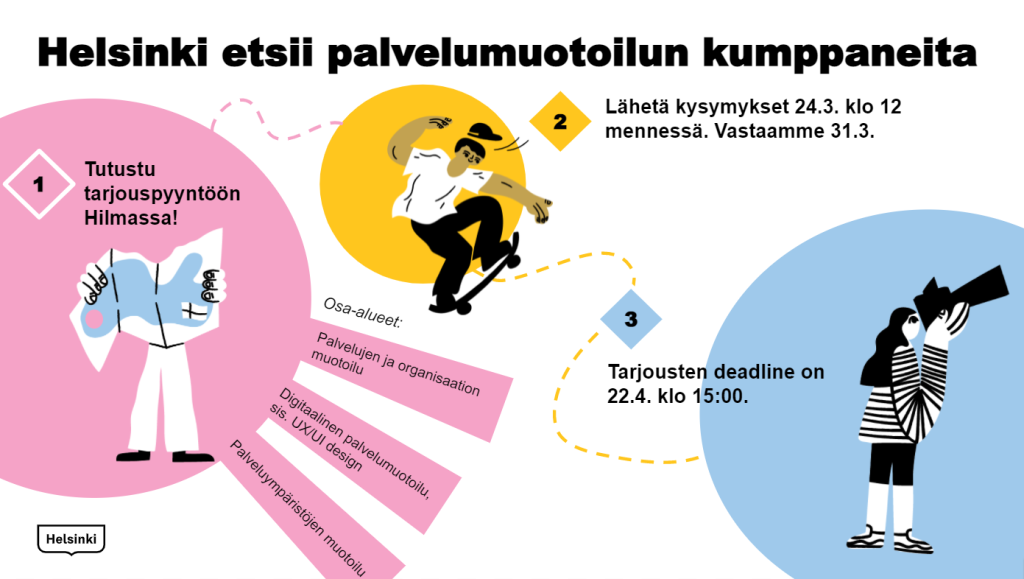

Background research allowed us to outline three areas for the upcoming tendering process:

- service and organisation design,

- digital service design , and

- service environments design.

It was clear that design activities should be increasingly focused on strategic levels and on understanding the future and systems.

Experiences of competitive tendering

Cities play an increasingly important role in addressing societal challenges. These include climate change, population ageing and marginalisation. We need tools and know-how to understand these phenomena. Our objective was that through the new partnership agreement we would also gain expertise in solving these wicked problems.

The competitive tendering was conducted through an open procedure, which sets minimum requirements for the tenderer and criteria for the quality of the work. Determining these criteria was a deep dive into the heart of design thinking for us. What do we really value?

What is the ‘meat’ in design, the thing that distinguishes it from other consulting sectors? And what skills do we need for our future projects?

We considered the criteria by areas. In addition to service design, we need skills such as customer research, organisational design and strategic design – management of change and understanding of public administration are also important. In the invitation to tender, we stressed that effectiveness and metrics are to play a key role.

We decided to assess quality using only one reference. For example, in area 1 – Service and organisation design – the service provider needed to show us one project tackling a significant societal or business challenge through design. This reference was assessed from three different perspectives – how the approach implements design thinking and, on the other hand, future orientation, and how the impact and benefits of the project were measured. In the digital service design field, however, usability research and content design were highly valued, and quality was assessed by means of a work sample, for example.

As expected, the range of criteria was vast in the field of service environments. Service environments consist of physical, social and virtual elements that together form the desired customer experience. This is why planning requires a comprehensive approach and a team with multidisciplinary expertise. The prerequisites for success in projects like this are management commitment and user-orientation, and the end result must support customer branding. All this was expected in the tenderer’s reference project. The more criteria we use, the more effort we need to put into comparison

The City Hall lobby is an example of a service environment that was created in cooperation between many different offices. The objective of the partnership agreement is that in such projects, the same office could be responsible for the service design, spatial planning and implementation. Image: Koko3.

Somewhat surprisingly, the most puzzling part of the tendering process was the impact of design activities. It was not an unambiguous concept after all. Despite our descriptions, the term was mixed with, for example, impact assessments performed for the customer. However, we used the term effectiveness to describe the objectives set for the design project and how the meeting of these objectives had been measured in this context. This makes the benefits and value of design visible.

The tendering process has now been completed and the new contract has entered into force. We received no fewer than 45 offers across three areas. Our new agreement now includes 12 great offices.

Lessons learnt

Public procurement in Finland is worth up to 35 billion euros annually. This means that public procurement is a tool for public administration to promote its strategic objectives and generate societal benefits. Therefore, framework partners are a strategic resource for the administration. Our new design partners have extensive competence and experience that we must be able to utilise during the new agreement period.

This type of tendering process is always laborious. Both for the customer and the tenderer. Overall, the user experience of public procurement needs improvement: there is lots of paperwork, the forms are dull, legal text is difficult and user interfaces are cumbersome. This does not necessarily need to be the case – public procurement can also be fun! The entire process would benefit from design: coupons could be laid out nicely, contents could be redesigned and user interfaces reshaped with the user in mind. Indeed, public procurement could do with a healthy dose of legal design. A user-friendly entity would be in everyone’s interest – it would perhaps also reduce the human errors that occur in these processes.

Public procurement would benefit from design. Visualisation, for example, could illustrate the key stages and dates of the process so that they do not need to be searched for in the material. Image: Anni Leppänen.

The tendering process was, of course, a major undertaking, but it provided us with a broad view of the field of Finnish design. Today, both companies and public administration use design extensively in renewing their services and organisation. Design is increasingly used in strategy work and solving important societal and business challenges. Operators have also been able to measure significant benefits – and effectiveness.

We also saw how much the sector had developed and the number and competence of design offices increased in just four years. Development had also taken place on the customer side, and new kinds of partnerships had emerged.

User-centered thinking has proved its strength, and design has been established as a development method – both in the private and public sector.

This is great news, as we are now taking our design journey into the next decade.

|

Päivi Hietanen is an architect who uses design to reform the city. She works as the City Design Manager at the City of Helsinki. |

Photos: Sakari Röyskö, Koko3, Anni Leppänen, Laura Oja